- Home

- Caroline Misner

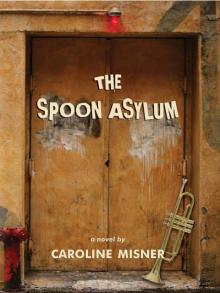

The Spoon Asylum Page 21

The Spoon Asylum Read online

Page 21

“We need more than that,” Bess said.

“Sorry, but it’s all we know of him,” Wetherby replied and turned to Haven. “I think it’s time.”

Limpid tears glimmered in Gertie’s eyes when Haven blew “Nearer My God to Thee” out of the corner of his mouth on her husband’s old trumpet with the frayed tassel swinging from the middle key. A tender nodule of bruised flesh on the top of his lip made Haven wince. His mouth was still swollen from his skirmish with Jude. Wetherby leaned on his cane, catching his breath to the wind. Eleanor hooked her arm through her mother’s scrawny elbow and drew her close; Charlotte dipped the brim of her hat over her eyes.

“Well, I suppose that’s it,” Wetherby said after a brief moment of silence. Haven placed his trumpet in its case and snapped the lid shut.

“I hate to leave him here, alone like this,” Gertie said.

“He ain’t alone,” Wetherby replied. “He be playing his mouth organ with the angels now.”

The meagre congregation slowly disbanded, wandering off in separate directions. No one else had bothered to attend the service. Ted Brandish forbade the boys of Camp Hiawatha to attend. Eleanor guessed it was because he didn’t have the courage to face her after his threats. The bus to Camp Nokomis stood vacant in the laneway. Eleanor had telegraphed the girls’ parents informing them of an accident that had occurred and advising them to pick up their children a few days earlier than scheduled. There would be no closing ceremony round the campfire that year. Charlotte elected to stay behind, claiming she couldn’t leave until she saw that Marcus was buried in a proper grave. She pulled away from Eleanor’s embrace and trudged toward the bus, her skirt lapping at her knees.

“Come with me this way, Haven.” Eleanor guided Haven down a path that led toward the old section of the cemetery.

Haven followed her. The tombstones were weathered and in disrepair, their inscriptions long since faded or filled with dirt until they were illegible. Few flowers garnished them. Most leaned awkwardly to one side, as though a strong wind had tried to push them down but given up. Some were massive, looming over six feet tall, topped with spires or carved angels, their features deteriorated by the elements. They stopped before a nondescript marker. It looked no different than any other neglected grave in that corner of the churchyard. Overgrown weeds sprouted round its base. Someone had left a small bundle of pink roses with rust curling the petals just below the epitaph.

“I’ve owed you an explanation for a long time, Haven,” Eleanor began. “I suppose you know by now that Bess Washburn, your grandmother, is my mother.”

Haven nodded, remembering the photograph on the shelf in Bess’s parlour. The two girls were nearly indistinguishable, though they were not twins.

“Are you my mother?” he asked. A small part of him hoped she was.

“No.” Eleanor shook her head. “I’m not your mother. But I am your father’s wife.”

Haven stared at her, unable to bring the two concepts together. Eleanor pointed at the tombstone.

“This is your mother’s grave,” she explained. “She died in 1918, when you were barely three years old.”

Haven stared down at the meaningless lump of chiselled stone. So this was his mother. He didn’t expect he would fall weeping upon her grave but he’d always expected to feel something — anything — if he ever saw it. To him it was just a stone, a chunk of granite with a woman’s name hewn into it. There could be anyone buried beneath the burnished grass and decaying roses. He felt hollow inside. He didn’t have the strength left to grieve for another.

“Your father and I were married for several years,” Eleanor continued. “We never had any children. I suppose it was my fault. Somehow, I just couldn’t see myself as a mother figure. My sister Estelle loved dancing and music, all the things that didn’t interest me. When our father died in the summer of 1915 we came to help out. We only intended to stay until the fall. Before we knew it, we had made a home for ourselves right here in Davisville.”

Haven listened, wondering what any of that had to do with him.

“I should have noticed right away. Harry and Estelle were spending more and more time together, listening to music and singing and dancing. I never cared much for that so I’d let them entertain themselves while I stayed at home with Mom and helped her around the house. Then one night I caught them together on the front porch. I thought I was dreaming. I couldn’t have imagined they would do such a thing to me, to the family, to the whole community. Do you understand what I mean?”

Haven nodded.

“When you were born, I was devastated. Estelle tried to keep it a secret for as long as she could. It would have scandalized the community and shamed the family. But after six months, it became apparent even to me that she was carrying my husband’s child. I couldn’t take it anymore. I left. I never saw her again. By the time I returned home, she was already dead and your father had taken you away.”

A memory solidified in Haven’s mind like a slide slipping into a stereoscope and the two images clarifying into single vision. He was young, little more than a toddler. He was wrapped in a blanket and slung over his father’s shoulder like a sack of flour. Bess’s house was in a better state then. The paint gleamed white as milk, the front porch where Bess stood and watched helplessly was sturdy, the steps even; roses bloomed like a rosy mist all round the foundation. He’s my son! Harry bellowed over his shoulder. He goes with me! Haven was crying and reaching for Bess, fighting against his father’s grip even as Harry hauled him into the car and slammed the door. Haven pressed his hands against the window as though his touch would make the glass melt away and he could crawl out. Harry put the car in gear and sped away in a flurry of dust.

“The bastard,” Haven mumbled.

“Yes, he was,” Eleanor agreed and squeezed the bony nub of his shoulder. “He was a right bastard. I never forgave him, or my sister. I just couldn’t reconcile what they did to me. But I went on with my life. I bought the land on Lake Manito and opened up a sister camp to Camp Hiawatha. Ted Brandish was a dear friend back then and he loaned me the money to get started. You can imagine my surprise when you showed up in my office looking for a job fifteen years later.”

Ribbons of cool air whipped the first of autumn’s dying leaves in spirals around the grave. A green mottled leaf slapped against the stone and partially covered the name: Estelle Washburn, 1898-1918, Beloved Daughter. A petal broke free from one of the roses and was promptly whisked away.

“I’m ready to go now,” Haven said.

Wetherby doddered up the path toward them. His back was humped over his cane, his head bowed against the wind, clutching his hat with his free hand. He was gasping for breath by the time he reached them.

“Miss Nokomis,” he wheezed. “I need a ride to the police station. Just got word from one of the townsfolk. They ready to take Judy now.”

Constable Seaver leaned over his desk and stared at the two men who sat in creaking chairs before him. Jude was strangely calm. Wetherby looked on solemnly. Nothing like this had ever happened in Davisville before. At first Seaver didn’t know what to do. His mind had still been reeling from the fire at Camp Hiawatha the night before when Jude had crawled into his office. Jude had kneeled at the threshold, little more than a pathetic lump of sweat-drenched flesh in singed clothes. Jude was babbling, entreating Seaver to lock him away and swallow the key; he was no good to anyone.

“I didn’t mean it!” he had bawled. “I didn’t want to hurt nobody! He was like a brother to me! It’s my fault, all my fault!”

It took Seaver several hours before he could calm Jude down long enough to extract a confession out of him. By then Jude was shaking and yanking clumps of hair from his head. Seaver had to restrain him with handcuffs before he hurt himself further. Seaver sat in the cell with him and listened as Jude explained how he had doused the lodge with kerosene and set it alight before fleeing back into the woods where he remained hidden for several days, surviving in berries an

d lake water.

“I didn’t mean to hurt nobody,” Jude had wept into his hands. “I was just so . . . so mad! I didn’t know what else to do. Now I goes and kilt my best friend, my brother. I’d never forgive myself if I hurt them little boys!”

“Calm down, son.” It seemed as though Seaver hadn’t stopped saying that to Jude since his arrival. “Just calm down.”

“What’s going to happen now?” Wetherby asked. They sat silently in his office, listening to the clock tick away the minutes.

“I’m not sure,” Seaver replied. “Arson is a serious crime, especially if it leads to a death. But the fact is I’ve never seen a situation where a coloured man kills a vagrant. It just doesn’t happen here. The truth is nobody really gives a damn about either one of them.”

Jude lifted his red-ringed eyes toward Seaver. He looked pinched and emaciated, like a man condemned and ready to accept his fate.

“Judy going to jail?” Wetherby asked.

“Probably at first.” Seaver leaned back, sighing. “But given the state of his mind right now, I’m pretty sure he’ll end up in a sanatorium eventually. It’s up to the judge in the Sault.”

A soft tap at the door made all heads turn. An RCMP officer stepped into Seaver’s office, graciously pulling his hat from his head. The two officers exchanged looks of recognition.

Seaver grinned and said, “Hey Bobby! I haven’t seen you in ages. Look at you now. Made it all the way to the ranks.”

“Mr. Seaver!” Bobby laughed. The two of them vigorously shook hands and slapped one another on the back. “How’s Jenny? How’s the baby. She must be getting big by now.”

“Growing like a weed every day,” Seaver replied. “Just like you. Boy, I remember when you were no bigger than my knee.”

Jude and Wetherby watched the two men exchange niceties and small talk. Bobby was not much older than Jude. His hair was trimmed and faultlessly combed. His jaw was closely shaved until his skin gleamed raw and rosy; a small bandage crisscrossed his left cheek. His uniform was immaculate; the epaulets on his shoulders gleamed brand new as though this was his first assignment. His leather boots shone like black glass.

“Is this him?” Bobby tossed his head in Jude’s direction.

“This is him, Jude Moss,” Seaver replied.

Bobby turned and bowed over Jude, extending his hand.

“Good day, sir,” he said. “I’m Constable Robert Monroe. I’ve come to escort you to Sault Ste Marie.”

Jude stared at the hand; no white man had ever offered to shake his hand before. He glanced at Wetherby, who rose and clasped Constable Monroe’s hand.

“Good day, sir,” he said. “I’m Wetherby Moss, Jude’s father. I’m afraid he ain’t feeling just right today.”

“That’s understandable.” Monroe squinted at him. “By the way, are you the same Wetherby Moss from the jazz group the Morrison Moss Quartet?”

“That be me.”

“It’s certainly a pleasure to meet you, sir!” Monroe grinned and pumped Wetherby’s hand ever harder. “I’m a big fan. ‘Walking Shoe Blues’ has been my favourite song since I was a kid.”

“Wasn’t that long ago,” Seaver snickered.

“I had to listen to your records in secret,” Monroe continued. “My folks wouldn’t let me listen to jazz in the house. They called it the devil’s music, but we all know that’s not true.”

“I’m mighty glad you enjoy it.” Wetherby pulled his hand back.

“Will you be making any more records soon?”

“Don’t think so.” Wetherby shook his head. “The Morrison brothers is long gone, and me and Judy, well, we got some bigger problems right now.”

“That’s a shame.” Monroe slipped his hat back on his head. “Well, I suppose we better get going. It’s a long drive and I want to get back before it gets dark.”

“It was nice seeing you again, Bobby,” Seaver said.

“Give my best to Jenny and the girls.”

Jude rose. His shoulders were hunched as though the handcuffs that rattled round his wrists weighed him down; he stared at his feet as he shuffled toward the door. Wetherby followed him, twisting his hat nervously in his hands, his cane tapping lightly against the floor.

“I’m sorry, but you can’t come with us.” Monroe held his arm across the door to bar his exit. “Regulations. You understand.”

“But I’m his daddy.”

“I know, but regulations stipulate that only the accused can ride along with me,” Monroe said. “For security reasons. You’re free to travel to the Sault on your own and meet us there. Then you can visit with your son as long as you please.”

“We ain’t been apart in years,” Wetherby said.

“I’m sorry.”

Wetherby stood back and slipped his crumpled bowler on his head. Seaver held the door open for Monroe. Jude didn’t look back at his father as he followed him outside.

CHAPTER 18

CHARLOTTE STOOD ON HER TOES and tightened the knot at Haven’s throat before planting a soft kiss on his mouth. Haven flinched under her touch. His mouth was still tender but healing rapidly. They’d been doing that a lot lately, stealing kisses from behind the woodshed or late at night on Bess’s front porch as they watched the fireflies flash neon specks into the night while they discussed their future together.

He tugged at the tie that bound his neck. He’d never worn a suit before and he felt silly and over dressed. He wondered how he had ever let Charlotte talk him into buying it.

“You look so dapper,” she said and smoothed the lapels of his jacket before stepping back to admire him.

“You look pretty good yourself,” Haven replied and placed his fedora on his head.

The train sat chuffing by the station platform, blowing bits of dried leaves from beneath its wheels. A few passengers had already boarded the cars, passing their tickets to the conductor who loitered by the doors, looking weary and unconcerned as he wandered up and down the platform, glancing in their direction as though imploring them to hurry, they hadn’t much time. Haven and Charlotte’s luggage sat at their feet with their clarinet and trumpet cases. Bess and Wetherby stood arm in arm beside them, looking on.

“Are you sure you want to do this?” Bess asked.

“Positive,” Charlotte replied.

“What about your parents?”

“I’ll send them a telegram from Chicago.”

Bess and Wetherby exchanged wary glances. Even though she was dressed in an immaculate grey suit and a handbag with matching shoes, Charlotte seemed far too young and callow to be venturing into the world on the arm a young man just as inexperienced as her.

“It ain’t an easy life,” Wetherby warned. “You two be playing for nickels on street corners just so you can eat.”

“I’m ready for it,” Haven said. Wherever his trumpet guided him, he would follow. He had never been so sure of anything in his life. Wetherby passed him a scrap of paper. Haven unfolded it and read the names.

“Look these folks up when you gets to Detroit,” Wetherby said. “I don’t read or write so good, but their names is all on there. Lonny Speckle, Agrippina Holmes, Big Boy Jack Thompson. Tell them I sent you. Them good people. They take good care of you.”

“Thanks.” Haven folded the paper and slipped it into his breast pocket. “I’ll be sure to do that.”

“If you ever make it to Chicago, look up my old pal, Louis Armstrong,” Wetherby said. “He be the greatest jazzman that ever lived.”

Charlotte’s mouth popped open.

“You know Louis Armstrong?”

“Met him years back on train bound for Chicago,” Wetherby explained. “Man, can that cat play the horn.”

“I want you both to write and let me know how you’re doing,” Bess said. “You have your tickets? Money?”

“Right here.” Haven patted his bulging pocket.

“I got one more thing for you.” Wetherby lifted a rumpled paper sack that he’d been hauling all day.

He handed it to Haven. “Go on, open it.”

Haven unrolled the top and gasped.

“I can’t take this,” he said.

“Yes, you can.” Wetherby grinned. “Go on. Take it. I want you to have it.”

Haven pulled Wetherby’s trumpet from the bag. It had been carefully polished until its brass gleamed gold in the early autumn sun. Haven turned it over in his hand. Tiny nicks and scratches that he had become so familiar with had been buffed from its surface. He could still feel the warmth of Wetherby’s hand upon it, the heat of his breath pumping through it.

“But this is yours,” Haven choked. A pebble had inexplicably become wedged in his throat.

“Not no more,” Wetherby said. “It be the horn I first played and now it be the last. It’s yours now. I ain’t got the breath to play it no more. You start out just like I did when I was your age, making the rounds with your horn in a paper sack.”

Moisture prickled Haven’s eyes. He longed to blow a few notes on it but his mouth flooded with water. He fluttered his lids and swallowed until the pebble slipped down his throat. Invisible wires tugged the corners of his mouth. Charlotte slipped her arms around his shoulders and he leaned into her until his mouth stopped trembling.

“Thank you,” he whispered. “But now I have to ask you a favour.”

“Anything.”

Haven picked up the trumpet case at his feet and handed it to Wetherby.

“This is Gertie Follows’ trumpet,” he said. “Will you please give it back to her for me? Tell her I appreciate her letting me borrow it, but I have my own horn now.”

“It be my pleasure.”

Haven removed his mouthpiece from Gertie’s cornet and placed it on Wetherby’s trumpet. It was a perfect fit.

Bess patted the corners of her eyes with a white handkerchief with the initials WB embroidered into one puckered corner.

The Spoon Asylum

The Spoon Asylum