- Home

- Caroline Misner

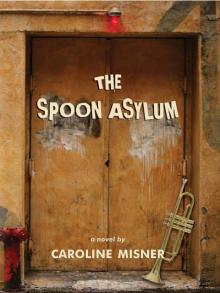

The Spoon Asylum

The Spoon Asylum Read online

©Caroline Misner, 2018

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Thistledown Press Ltd.

410 2nd Avenue North

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7K 2C3

www.thistledownpress.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Misner, Caroline, 1966–, author

The spoon asylum / Caroline Misner.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77187-155-6 (softcover).—ISBN 978-1-77187-160-0 (HTML).—ISBN 978-1-77187-161-7 (PDF)

I. Title.

PS8626.I823S66 2018 jC813'.6 C2018-901139-4

C2018-901140-8

Cover and book design by Jackie Forrie

Printed and bound in Canada

Thistledown Press gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Saskatchewan Arts Board, and the Government of Canada for its publishing program.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CHAPTER 1

SMALL BIRDS ROSE IN CLUSTERS at the approach of the train. Warbling in protest, they spiralled and zipped across the stark azure sky; smoke from the engine heaved upward and dissipated in long misty trails. The train had begun to slow once it approached Davisville. It was now on its way to Gravenhurst, where it was scheduled to stop, hauling its queue of boxcars and cattle cars behind it like a drowsy snake. Heat and wind from the whining wheels flattened the spiky grasses that flanked the tracks. Small farms and homesteads that had somehow managed to thrive despite the rocky terrain and dry bitter soil of the north looked on with windows winking in the hot June sun.

The door to one boxcar slid open. Several men in shabby clothes too warm for the season leapt out, dropping into the brittle grass like hailstones, arms flailing and coats billowing out behind them. Marcus was among them. His bedroll, the only possession he carried, bounced against his back when he tumbled from the freight car, landing hard on bended knees. The bright sun temporarily blinded him and he squinted from under the brim of his cap as the train chuffed past. He had spoken little to the other men during the journey, and he didn’t care to speak to them now. He had been content to slouch in the corner of the car between two massive crates of salt cod bound for the prairies and play his harmonica. The dried fish gave the thick air a salty, fishy tang, scalding his eyes and making them feel dry, though they watered. He tried to play the best he could with sweat trickling down his brow. The other men didn’t seem to mind. After a while they began calling out requests:

“Play ‘Oh, Susanna’!”

“Do you know ‘Wrap Up Your Troubles in Dreams’?”

“How about some ‘Home, Sweet, Home’?”

“Ever heard of any jazz?”

The last question came from a grey-whiskered, pinched-faced man sitting on a crate, gnawing on a piece of salt cod.

“I’ve heard some,” Marcus admitted.

“Do you know ‘Walking Shoes Blues’?” Grey Whiskers asked. Marcus shook his head and cleared the harmonica by blowing a series of shrill notes across it.

“Best damn jazz song I ever heard.” Grey Whiskers tipped his hat down over his woolly eyebrows and closed his eyes, leaning back against the crate as though the song played through his head.

Marcus shrugged and turned away. He had no desire to pursue a conversation with that man or anyone else in the boxcar. He disdained their company, preferring to sit alone in the corner rather than listen to their bickering and grievances as they blamed everyone in the world for their troubles but themselves.

When they trudged along the track toward the open field, he offered them only an indifferent wave, breaking away to follow his own path.

He had spotted the farmhouse before jumping from the train. Even from the distance he could see it was old and in disrepair, with weathered shutters and dingy walls. But it looked inviting. A line of laundry sagged between the back porch and the wood shed, awaiting whatever breeze the air could offer. Black specks jerked back and forth across the back yard. Chickens, he thought. A good place to find a meal, though he didn’t balk at pilfering a piece of salt cod while on the train, just in case. He pulled his harmonica from his pocket and played a slow sleepy rendition of “The Old Folks at Home” as he lumbered toward the house, pushing tall weeds out of his way.

Dust blew in through the opened window of Harry Cattrell’s roadster as it whined to a stop in front of the house. He was amazed how the property had deteriorated over the past fourteen years when Harry had packed up his son Haven and left for good, vowing never to return. A rusty mailbox with the name “Washburn” scrawled across it in faded letters roosted atop a post that leaned so far to the right it was a miracle the mail didn’t slide out. The fence had been white once, but now strips of greying paint peeled away from the pickets in long thin flakes, revealing the scarred wood beneath. A dilapidated rocking chair swayed on the saggy porch of its own accord, as though a ghost inhabited its threadbare wicker seat. Scraggly rose bushes huddled round the stone foundation, hoarding hard green nubs on their prickled stems. Dry grass wavered in the hot wind, its greenness dulled by a fine film of dust. It was still too early in the season for the grass to be so dry. It crackled under his shoes as he stepped out of the car. Haven followed, dragging his feet and hauling a heavy leather valise with brass corners.

“You don’t remember this place do you?” Harry asked his son.

Haven shook his head. He’d spoken little to his father on the drive from town, a silent protest that only built a barrier between them.

His grandmother stood behind the door, wiping her hands in her apron. Her face was veiled by the screen; it was impossible to guess her expression. Harry stood on a patch of limp weeds and pulled his fedora from his head, twisting the brim out of shape as he pressed it against his chest.

“Hello, Bess,” he said. He stopped short after another step. Haven stood behind him and watched a tepid breeze swirl dust in small cyclones around his shoes.

“What are you doing here?” Her voice was as smooth and crisp as freshly pressed linen. If Haven closed his eyes he could have sworn he was listening to a cultured young woman his own age.

“Surprised?”

“Disgusted is more accurate a word,” Bess replied and pushed the door until it swung open with a screech.

“Didn’t you get my telegram?” Harry asked.

“I got it.” Her lashless eyes rolled in Haven’s direction. Everything about her was grey and bleak. She looked as though the indomitable winds had buffed all colour from her being the way they had brushed the topsoil from the plains.

“Is this him?” she asked.

“I’m Haven.” It was a statement rather than an introduction. He placed the valise on the grass and approached the porch, feeling a snap under his feet as he climbed the first step.

“You might as we

ll come in and sit awhile.” Bess stepped aside so they could enter the house. Harry remained in the front yard and slowly backed away toward the car that sat idling and sputtering by the gate.

“No thank you,” he said. “I have to get going.”

“Already?” Haven glowered at his father.

“It’s just till the end of the summer,” Harry replied and placed his rumpled hat back on his head before slipping in behind the wheel.

“Wait!” Haven leapt from the porch and ran toward the car as the engine surged. He gripped the edge of the window. “Don’t leave me here!”

“I have to.” Harry stared at the windshield, spotted with the viscera of dead insects. He refused to look his son in the eye.

“Take me with you,” pleaded Haven. “I could work at the camp. I’m old enough, I’m strong. I hear they hire boys as young as twelve at these places.”

“I’m sorry. I can’t.” Harry shook his head. “I’ve got to go, Haven. You stay here and mind your grandma. I’ll be back. I promise.”

The car slipped out from under Haven’s hands and spewed plumes of dust in his face, coating his hair and lips with grit. He watched it disappear down the dirt road, the spare tire on the back receding like a black unblinking eye. Haven coughed into his fist and ground the grit in his mouth, feeling the crunch under his teeth.

“You bastard!” he screamed into the settling dust.

Bess leaned her wizened arms against the porch railing and watched. He was so much like his mother her heart plunged under a lump of renewed grief. The lad was tall and lean, almost a man, with the same unkempt tawny hair and the same deep set eyes of burnished blue. The last time she had seen him was the autumn of 1918. Harry had been carrying him bundled in a quilt toward the car from his mother’s grave. Haven howled and cried and reached out toward her with pink plump hands.

Haven twirled around and kicked at a stone, sending it spiralling toward the gate where it struck the splintered wood with a dull thud.

“Bring your things in,” Bess said. “I’ll show you where you’ll be sleeping.”

“I’m not staying,” Haven declared.

“Do you mean ever, or just for tonight?” Bess asked.

“I mean I’m not staying,” Haven said and grabbed the handle of his suitcase. His few belongings rattled inside.

“And where do you plan to go?”

“To the camps.” Haven cocked his head toward the road. “To look for work. They’ll hire me.”

“The nearest government relief camp is a good three days walk away,” Bess replied and turned to enter the house. “You can start now and sleep in the woods or you can come in and get yourself cleaned up for supper.”

The screen door screeched shut behind her.

Bess handed him the axe and pointed to a pile of wood stacked in a lopsided pyramid beside the chicken coop. Haven stared at it, unsure of what to do. The axe was heavier than he’d expected. He’d only seen people wielding axes in the matinees he watched at the Tivoli Movie House in Hamilton and they made it look easy, like swinging a baseball bat. He gripped the smooth handle and the head drooped under its own weight.

“As long as you’re staying here, you may as well do some chores,” Bess said.

“I don’t know how to work this thing.” Haven heaved the axe blade upward and almost tumbled into the dust.

“Well, you better learn!” Bess laughed. “If you want to go work at the lumber camps with that no-good deadbeat father of yours.”

“I’ll do something else.”

“Like what?” Bess stopped laughing and scowled at Haven. “Now you get to work on that wood. And when you’re finished, clean and dress one of those chickens for our supper.”

“What?” Haven wasn’t sure what she meant, but he suspected it wasn’t a pleasant chore.

As though on cue, a brown hen broke away from the flock and scampered toward Haven, her scarlet comb and wattle flapping with each bob of her head. She stopped and pecked at the ground at Haven’s feet. He yelped and skipped backward, swinging the axe like a club in her direction. The hen lifted her feathered head and regarded him indifferently as the blade whizzed over her head. Bess clicked her tongue and rolled her eyes.

“I’ll be inside doing the wash,” she said and climbed the steps to the back porch. “I’ll be back later to see how you’re doing.”

“What am I supposed to do with this thing?” Haven pointed the axe toward the chicken, who had resumed scratching and jabbing her beak into the ground.

“Kill it,” Bess replied as she pushed her way through the screen door. “And prepare it for the pot. A city boy like you ought to know how to pluck a chicken, right?”

Haven opened his mouth to protest but Bess had already disappeared into the depths of house.

“Bitch,” Haven muttered and the hen looked up at him with round glossy eyes.

He turned and stared at the chopping block, a thick oak stump with deep scars embedded into its surface. The first log he tried to cut teetered precariously on the stump and clattered to the hard packed ground with the first swing. His second attempt was a little more successful; he managed to pound the tip of the blade half an inch into the wood but couldn’t get it out again. He pounded it against the chopping block until the axe head stuck. Enraged, he pummelled the ground with it until dust bloomed up in soft clouds. He envisioned his father’s head at the end of the axe. The jackass, he thought. How dare he leave him alone in the middle of nowhere with this withered old crone who expected him to chop wood and kill chickens and do God knows what else? One thing he knew for sure: he was not staying a minute longer than he had to. He would find a job in Davisville, doing anything for anybody, until he saved enough money to catch the next train for home. Or better yet, to the nearest Relief Camp where he would hunt down his father and tell the old bastard exactly what he thought of him.

“You’re doing it all wrong.”

The voice startled him so much he dropped the axe and reeled backward, almost tripping into the ground.

“What?”

A young man, not much older than him, stood at the edge of the yard, a bemused smile creasing his dirty, unshaven face. The tattered brim of a cap shielded his eyes but Haven knew there was laughter dancing around in them. The hair that poked from under the cap was black as soot and powdered with dust. The man wore a long black overcoat; he must have been sweltering in the midsummer heat. He carried a bedroll slung over his back and fingered a harmonica that gleamed like a gem in the sun.

“Need some help?” he asked.

“Who are you?” Haven demanded.

“The name’s Marcus,” the young man replied. “I’m just passing through. I thought you could use a little help. You sure don’t look like you know what you’re doing.”

“Be my guest.” Haven lifted the axe by the handle, heavy from the weight of the log, and passed it to Marcus.

Marcus shrugged out of his coat and draped it over the fence with his bedroll, tucking the harmonica into a side pocket. He tipped his cap back and Haven could see the sweat glisten on the stubble of his chin. He pressed the log into the ground under his battered shoe and pulled the blade out with one deft movement.

“The trick is to put all your weight into it when it falls,” Marcus explained as he placed the log on the chopping block. “Try to get it down the middle. Once the axe is in, all it takes is a few light taps and it’ll just split in two. Like this.”

Marcus swung the axe in a wide arc over his head, cleaving the log in half. A piece of wood flew at Haven; he had to duck to avoid getting hit.

“Want to try?” Marcus held the axe out to him.

“No, you go ahead,” Haven replied. His hands were numb and stung with fresh blisters. He wiped them in the seat of his pants.

“It’s not that hard.” Marcus set another log on the block and chopped it in two.

“Where did you learn to do that?” Haven asked as he watched more split wood pile up around Marcus’s

feet.

“Don’t know. Just learned it along the way.” Marcus wiped the sweat from his upper lip on his shoulder.

“Do you know anything about killing chickens?” Haven asked.

Marcus laughed and glanced at the hens that pecked and wobbled around the yard. The brown hen had rejoined the flock and Haven couldn’t distinguish her from the rest.

“You got to do that too?”

“My grandma Bess wants me to kill a chicken for supper,” Haven explained, cocking his chin in the direction of the house.

“You’re not from around here either, are you?” Marcus leaned on the axe like a cane.

“How’d you know?”

“Anyone who grew up around here would know how to chop wood and dress a chicken,” Marcus replied. “I’ll tell you what. Go out there and get me a nice fat one. I’ll kill it for you if you promise to share a piece or two of that chicken with me. I’m not picky about what I eat. I’ll even take the neck or the feet.”

“All right,” Haven nodded. “But I’ll have to ask the old lady first.”

“Fine.” Marcus pointed with the axe. “Go fetch me that wash pan and fill it with water from the pump.”

Haven had no idea how to capture a chicken, or how to handle it once he caught one. Each time he approached the flock, the hens scattered in a blur of feathers and talons, squawking and flailing their wings. Haven pursued each one in turn, pouncing whenever he thought he was near enough to grab it. Sharp beaks pecked at his hands and forearms, leaving small pockmarks in his skin. He didn’t want Marcus to see that he was scared of them; after all they were only chickens, the dumbest birds in the world. Marcus leaned back against the pump, the pan of water at his feet, and laughed at Haven’s fumbled attempts.

By the time Haven caught a black and white speckled hen with a torn comb, he was glazed with sweat and bleeding from the scratches on his arms. The hen protested loudly, cackling and struggling under his grasp. Haven held her at arm’s length, afraid the bird would peck out his eyes.

“Hold her by both legs and bring her here.” Marcus lifted the axe and approached the chopping block.

The Spoon Asylum

The Spoon Asylum