- Home

- Caroline Misner

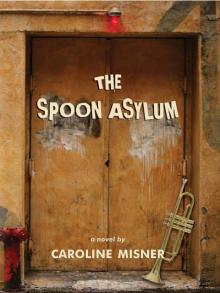

The Spoon Asylum Page 13

The Spoon Asylum Read online

Page 13

By August Pa devised a new act. Charlene leapt onto the table where she used to sit and danced on top of it, kicking up her legs until we could see her stockings rolled to the knees, and her skirt fly around her like an umbrella. She kicked over whatever happened to be on that table: glasses of hooch, ashtrays, even the little potted candles. Normally the patrons at that table would have protested bitterly. Instead, the lady who was sitting there, a horse-faced redhead with big floppy bosoms, jumped on the neighbouring table and joined Charlene in the dance. After a few more bars, she had every lady in the joint dancing on their tables while the poor waiter scurried about on his hands and knees and squelched the candles with a wet bar towel. We made a tremendous mess that night, but Adams didn’t mind. For every drink that got spilt, another had to be bought and he made a hefty profit. We never saw a nickel of it and I don’t think Charlene did either. After that first night he had all the candles replaced with little tin pots of silk flowers because they wouldn’t break when the dancing women kicked them over. It didn’t matter to me either way; I still had to clean up the mess at the end of the night.

“Man, you must be either the bravest coons I’d ever met or the dumbest,” Scotti said at our last rehearsal. Miss Charlene and Pa were working on a new act where they would dance together around the stage. Pa was hoping to get the gentlemen up on their feet and working up a thirst.

They made quite a pair. Pa was so much larger than Charlene her waist disappeared in the cup of his hand when he placed his palm just above her hip. If they had been more proper, or at least more discreet in the company they were in, they would have paid more mind to what they were doing. In Charlene’s defence, I must admit that given Pa’s girth, it would have been impossible for a small woman like her not to touch his body with her own when they danced. But they could have at least tried. The instant their hands touched and their bellies pressed together, it was evident to all of us watching. A closeness had bloomed between them over the summer, but Pa was no idiot. He knew his place at the club and in society; he maintained a respectable distance, though he never balked at the opportunity to hold Charlene’s hand when she climbed onstage.

“So teach me to dance with you, Mr. Wetherby,” Charlene said and gazed up into his eyes. At that moment she must have really believe that they were the only two people in the room.

Scottie leapt from his barstool and charged into Adams’ office where the steady click-clack of the adding machine tallied up the previous evening’s receipts. By the time Adams bolted up the stage steps, Pa and Charlene were fox-trotting to Sass’s clarinet and laughing like the world around them had disappeared.

“What the hell is going on here?” Adams demanded. He yanked Charlene off Pa so hard her blouse tore open at the collar and little opal buttons sprung into the air like hailstones. Charlene gasped and clutched her arms around her chest.

“We were just dancing . . . ” she stammered.

“You little whore!” Adams bellowed and shoved her toward his office.

“Please, Honeycakes, I didn’t mean nothing,” Charlene pleaded as he hauled her into his office and slammed the door.

We saw Adams raise his fist behind the little window. It dropped like a rock and smacked into something soft. Miss Charlene cried harder than she had that first night Pa met her. Adams grunted with each blow; all the while she pleaded him to stop, calling him all sorts of sweet sounding names like Babycakes and Honeybuns.

We stood rigid in our places, our instruments still in our hands. We were embarrassed to be privy to what was going on, and helpless to stop it. The look on Pa’s face could have cracked stone. He stomped toward the edge of the stage, rolling his shirtsleeves to his elbows and loosening his tie.

“Don’t Pa.” I caught his arm before he could descend the stage. “It ain’t worth it.”

“I’ve got to do something,” Pa hissed.

“We all want to,” I admitted, “but we can’t. We’d be risking our own necks.”

“He ain’t no gentleman,” Pa scowled.

“He never claimed to be,” I said.

We expected Adams would order us to gather our instruments and get our black hides the hell out of his joint. Instead he reneged on his promise of free hooch and meals and worked us harder than ever. We had one fifteen minute break at midnight, which I spent gathering piles of dirty glasses and Pa spent wheezing at the bar. Miss Charlene never came back to the Adams Apple and I never saw her again.

Jude paused to quash his cigarette butt under the heel of his shoe. Marcus solemnly passed him another. Charlotte drew her long legs up to her chest and wrapped her arms around her knees, skulking back in her chair. Haven leaned toward her, overcome with a longing to touch someone, anyone, offer whatever comfort he could. Somehow, he envisioned Mabel’s face in Charlene, and the thought of her suffering under the malice of a brute like Adams sent venom coursing through him. Jude stared at the floorboards, refusing to look directly at any of them.

“That poor woman,” Charlotte said. “Wasn’t there anything either of you could do to help her?”

Jude pinched his eyes shut and shook his head.

“What happened to her?” Haven asked.

Jude drew heavily on his cigarette and blew pillows of smoke out through his nose. It had grown dark while he talked and Marcus lit a lantern and placed it on the floor between them. Amber light filled the porch and magnified their shadows into animated giants against the wall. It was several minutes before Jude could speak again.

This is my daddy’s vision of the truth and I believe him:

Business was slow at the Adams Apple since Charlene left and we found ourselves playing to a half-empty house on most nights. This worked out fine for Pa. It had been more than a week since he indulged in his early morning constitutionals by the river, a ritual he observed and enjoyed after a gruelling night of blowing his horn. Since Adams worked us like mules, Pa had fewer opportunities to stroll the park by the river. Another blistering August day awaited him and he looked forward to a cool bath before napping away the hottest part of the afternoon.

He spotted the three women sitting on a red plaid blanket on a grassy patch between the path and the river, indulging in a liquid picnic. Their laughter was high-pitched and far too loud for such an early hour. When they spoke they all seemed to have something important to say, and chattered in unison so no one could be heard. Normally Pa would have passed them on had he not spotted that familiar pink hat hanging lopsided on her head.

“Miss Charlene!” he called just as she tipped the mouth of the flask to her lips. “Is that you sitting over there?”

The three women stopped tittering and their eyes rolled drunkenly toward the sound of his voice. Pa remembered one of them as the redhead who had danced with Charlene on the table.

“Mr. Wetherby!” Charlene swayed to her feet, dishevelled and bleary eyed.

“We really missed you down at the club,” Wetherby said. The other two women watched him warily.

“I don’t need Hugh no more,” Charlene declared, twirling around on her toes with the flask held over her head. Pa smelled the liquor on her even before she reeled across the grass toward him. It was evident she had been there all night with her friends, drinking herself delirious.

“You know this ain’t the proper way for a lady like you to be behaving,” Wetherby said and snatched the flask from her hand.

Miss Charlene reached for it, but in her drunken state toppled over into Pa’s arms. Smiling, she clasped her arms around his neck and swayed like a leaf on a tree.

“Oh Mr. Wetherby!” she teased and the ladies behind her alternately gasped and giggled. “You’ll be my new sugar daddy, won’t you?”

“Miss Charlene!” Pa gasped and pried her hands from him. “Don’t you go talking like that!”

“Give him a kiss!” the redhead called and her companion fell over laughing.

“Now this ain’t right!” Flustered, Wetherby wriggled from Charlene’s grasp. “

You ladies better get yourselves home and in bed before someone gets hurt.”

He tossed the flask on the blanket; the three women pounced on it like three hounds after a bone. The redhead glared at Pa for having the audacity to address them in such a manner. He turned and continued along the path toward home, their laughter and chatter jangling in his ears.

Miss Charlene’s two companions would later swear that they had seen her leave on Wetherby’s arm. But the truth is he left alone and no one ever saw her again. He should have taken her home and cleaned her up and put her to bed, but the rules of propriety at that time forbade it. It was a decision that’s harrowed him the rest of his life. Later that same day, Miss Charlene’s body was found in a ditch by the side of the road, the back of her skull smashed in by some sort of blunt object.

In his grief, Mr. Adams closed down the club and we were left without a job. He told his bouncers to let us in just long enough to collect our equipment and get the hell out. I thought he must be hiding something or perhaps blaming us somehow for Charlene’s death. Perhaps it was a little of both.

Pa took the news especially hard. He wouldn’t even get out of bed to play with me and Sass on the street corner for the pennies of the passerby. It was the only gig we could get on such short notice. Child Morrison had disappeared and not even his brother could find him. Child had a tendency of hitting the junk pretty hard when things got tough. When he did make an appearance, he’d be glassy-eyed and delirious, his arm all swelled up with little puckered punch marks. It would be days or even weeks before we cleaned him up enough to play.

We were a sorry duo on the street corner that day. I played my mouth organ to Sass’s clarinet, nodding a thank you to every passerby who stopped to listen and plunk a nickel or two into the upturned hat at my feet. We barely collected a dollar between the two of us, not even enough for a meal and a few cold beers to wash away the summer heat. It was dark by the time we climbed aboard Sass’s truck.

“Let’s head on home,” Sass said as the engine sparked to life. “I’m too beat down to go anywhere else tonight.”

I nodded, knowing he was just as concerned for his brother as I was for Pa, who was alone, brooding and weeping, in the little tarpaper shack we shared in a field outside of town.

A round buttery moon rose over an open field; the shadows of the trees mottled the road in ghostly light. We saw another set of shadows up ahead. At first we couldn’t distinguish their faces. Their car was stopped and cocked sideways, blocking our passage. Mr. Adams stood waving his arms, flanked by Scotti and Maurice. Sass inched the truck to a stop; I stuck my head out the window into the hot August night and opened my mouth to ask them if their car was broke or if they needed help changing a flat tire.

Maurice grabbed my arm and nearly yanked it from its socket before the door was fully opened. I stumbled into the grass as he bent his knee into my spine and fastened my hands at the small of my back. Sass made a thudding “oof!” sound when he hit the ground beside me. Gasping for breath, he staggered to his feet. His hands were bound behind his back like mine; Scotti rattled a chain like a string of bones and to my horror, I saw Maurice had one too.

“Over there!” Adams pointed to a pair of oaks behind some brush where we couldn’t be seen from the road. My heart thumped so hard I thought it would snap the chain that Maurice wound around my chest and legs. I was so scared my mouth went dry. Sass was bound to the other tree; his face was so wet and gleamed so brightly in the moonlight he appeared as white as the men before us. I thought of pleading for my life but my mouth was so dry and the chains so tight I couldn’t breathe.

Scotti and Maurice stepped back to admire their handiwork; Adams stepped out between them. He looked Sass over, smiled and turned toward me. He stood so close I could smell the sweat in his hair and see the pocked fissures in his craggy complexion. A toothpick jutted from the corner of his mouth. It was all I could see. Fascinated, I watch that slender toothpick dance back and forth across his lips.

“Where is he?” His voice was so placid and soft he could have been addressing a sweetheart.

“Who?” I choked on the dust that filled my throat.

“Don’t play games with us, coon,” Maurice snarled and stepped toward me. In his hand swung the noose they had prepared for my daddy’s neck.

“Ever been in love, coon?” Adams asked and the toothpick bobbed in his mouth. “Ever have the woman of your dreams, the light of your life, taken away?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” I stammered.

“Don’t listen to him, Jude!” Sass screamed across the few feet that separated us. “He never loved Miss Charlene. We all saw the way he treated her.”

“Shut him up!” Adams roared and Scotti gleefully thrust his fist into Sass’s gut; the chain rattled across his shackled chest.

“I’m going to ask you one last time and I’m going to ask you nice,” Adams snarled in my face. “Where’s your daddy?”

“Don’t tell him!” Sass wheezed and lifted his head. “We all know it was him who done it! Now he wants to go accusing poor Mr. Wetherby of something he didn’t do.”

“You’ve got a pretty smart mouth for a nigger.” Adams didn’t need to give instruction this time. Scotti smashed his fist across Sass’s face. A fountain of blood spewed from his lips.

“So where is he?” Adams stepped closer. The toothpick pricked me in the chin.

“I don’t know,” I said and silently prayed for Pa to be as far away as possible.

“You’re hiding him, aren’t you?” Adams accused. “We’ve been to your house. He’s not there. He wouldn’t leave town without you and he’s not smart enough to hide himself.”

“He don’t need to hide from nothing!” I couldn’t believe Sass’s audacity. Wasn’t he aware of the danger we were in?

“I ain’t seen him all day,” I blurted.

“I think the coon’s telling the truth,” Maurice said, squinting at me. “Look at him. His eyes are so big and bug-eyed they could be headlights.”

“You better be telling the truth,” Adams said and the toothpick snapped in his teeth. “’cause if you’re not we could get another rope for your sorry neck, too.”

“Let us go!” I pleaded, “We haven’t done nothing to you gentlemen.”

“Coon’s right,” Maurice said. “It’s Wetherby we want. We could let this one go.”

“And what about the one with the smart mouth?” Scotti cocked his head toward Sass who spat a foamy, bloody wad into his face. Scotti snickered and wiped it away with his sleeve.

“He needs to be taught a lesson,” Adams stalked toward him, “on how to have proper manners when addressing white folk.”

“Screw you!” Sass was so scared his voice was edged with tears. The trio of captors laughed at him.

The chain that bound me to the oak loosened and clanged to the gnarled roots at the base of the tree. I could finally breathe again.

“Go!” Adams ordered, “before I change my mind.”

I stumbled and groped through the brush toward the road where Sass’s truck still hummed and idled in the sultry night.

“What about me?” Sass screamed.

I didn’t have the mettle to turn and see what they were doing to him. Laughter hung in the thick air like wet laundry and Sass screamed again. I stumbled into the truck and groped for the gearshift. Sass’s voice gonged in my ears; I was amazed I could hear him over the roar of my heart.

“Jude! Don’t leave me! Help me, Jude! Don’t go! Help me!”

It was the last thing poor Sass Morrison ever said to me or anyone else. My heart ached for him. Oh, Sass, I’m so sorry for leaving you there like that, tied to a tree and at their mercy. Not that trash like them have a speck of mercy anywhere in their pitiless souls. I’m sorry, Sass. So very, very sorry.

I turned the truck around and lurched back the way we had come. I dared not turn on the headlights. I’m no fool. I knew the only reason they let me go was for bait t

o find Pa once they finished having their fun with Sass. I kept glancing in the rear-view mirror, expecting a posse of white folk in pursuit, waving pitchforks and torches.

I had to find Pa and get the hell out of Detroit. Even if it was proved that Pa never so much as touched Miss Charlene, the white folk in town would make our wretched lives even more miserable before driving us both into early graves. I knew he wouldn’t be at home. It wouldn’t have surprised me if Adams and his goons had set our tarpaper shack afire trying to smoke Pa out. I headed back toward the river, hoping Pa was somewhere nearby.

Music drifted through the darkness and drew me toward the cemetery. It was Pa’s trumpet, playing slow and sweet and so full of soul it could have lifted the dead from their graves. He stood over Miss Charlene’s grave, the moonlight casting silver speckles in the brass of his horn. Tears shimmered on his cheeks and plopped on the fresh mound of dirt that covered her grave.

“Pa!” I hissed, trying to keep my voice low out of respect for the departed. “What are you doing here? We’ve got to go!”

Pa pulled the horn from his mouth and looked at me, his eyes as round and full as the moon above us.

“Judy!” he said and I cringed. I always loathed it when he called me that. Judy is a girl’s name.

“I’ve come to get you, Pa,” I said and grabbed his arm to guide him to the truck, but it was like trying to pull one of the oaks out by the roots.

“But I haven’t finished playing for Miss Charlene,” Pa said.

“No time,” I replied, “You can play it later. Wherever she is, I’m sure she can hear you. Right now we have to leave.”

“Why?”

“Can’t explain right now.” He finally allowed me to guide him to the truck. “But our lives are in danger. We have to leave Detroit.”

“Is it because of that bastard, Adams?” Pa scowled as he climbed aboard.

“Yes, Pa,” I replied, “it is.”

I found Bootlegger’s Bridge behind a copse of pines. It was a makeshift suspension bridge tethering the banks of the Detroit River with a thick cord that could be easily cut if the bootleggers suspected the law on their tails. It had been used for years by rumrunners who smuggled their contraband across the river from Canada. I knew full well Adams’ supplies came across that very bridge twice a week.

The Spoon Asylum

The Spoon Asylum